War of the Austrian Succession (1740-8)

Mapping collected by William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland

Charles VI (1685–1740), emperor of the Austrian Habsburg Empire, died without a male heir but having set out the order of succession to be followed. Known as the Pragmatic Sanction, this provided that all the Austrian Habsburg lands were to be kept together and that his eldest daughter, Maria Theresa (1717–80), should succeed him. This Sanction was accepted by Hungary and the major European powers except for Bavaria, whose Elector, Charles Albert (1697–1745), claimed the succession for himself. Other claimants were Philip V of Spain and Augustus III of Saxony.

The supporters of the Pragmatic Sanction were the Habsburg Empire, Great Britain, Hanover, the Dutch Republic, Saxony, Savoy and Sardinia, and Russia. Among their opponents were France, Prussia, Spain, Bavaria, Saxony, Naples, Sweden, Hesse-Kassel, the Palatinate and the Jacobites.

The war was fought over a wide area, including the Low Countries, Italy, North America and India, with naval operations in the West Indies, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. It culminated in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, signed on 18 October 1748. Amongst its resolutions was the recognition of the Pragmatic Sanction.

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1721–65), fought his first major battle in the War of the Austrian Succession at Dettingen, on 27 June 1743, under the command of his father, George II (reg. 1727–60) – the last time that a British monarch led his troops into battle. The month before his 24th birthday, on 6 March 1745, the Duke of Cumberland was appointed ‘Captain General of all His Majesty’s land forces’ and took command of the allied army (British, Hanoverian, and Dutch) in Brussels in April.

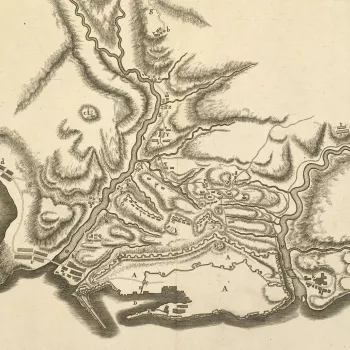

Over 500 maps and other graphic items that he acquired during the course of the war include a manuscript map of the Battle of Dettingen by his aide-de-camp, Robert Napier (c.1703–66), which is the first map known to have been commissioned by Cumberland. Also present are rough sketches showing projected march routes, camp sites – many of them prepared by his draughtsman, Schultz – as well as printed topographical maps, which were used for strategic planning and the recording of campaigns.

![Map of Eger [Egra], 1742 (Cheb, Karlovarsky Kraj, Czech Republic) 50?04'46" N 12?22'26"E](https://cmsadmin.rct.uk/sites/default/files/styles/rctr_scale_crop_350_350/public/728072%20crop.jpg.webp?itok=0ReqX6I6)