American War of Independence (1775-83)

George III’s maps and views showing the development of the war at home and abroad, from North America to India

The Encampment at Warley Common (Essex) in 1778

177848.0 x 147.1 cm (sight) | RCIN 734037

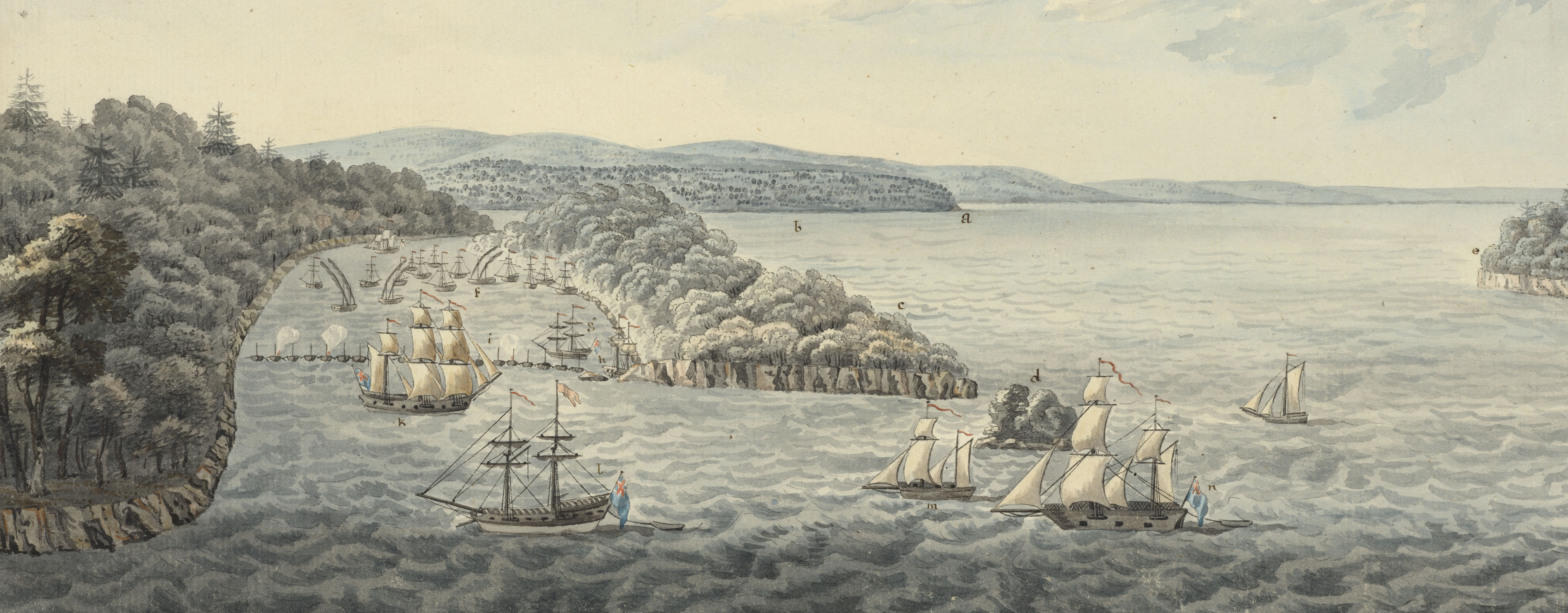

A view of the encampment on Warley Common 28 May-11 November 1778. American War of Independence (1775-83).

Originally described, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, as a view of the camp on Cox Heath, this watercolour has now been identified as the camp on Warley Common.

Three years after the onset of the American War of Independence (1775-83), a new military emergency arose from the decision of France to form an alliance with the American colonists against Britain. Within a short time, the British militia were called to arms to counter the possibility of a French invasion of England. There ensued a spread of military activity across the country – ‘From camps to fleets, from Plymouth to Coxheath’ as one contemporary ditty put it. Encampments, ranging in size from a few hundred to several thousand men, transformed the social and economic life of the locality for their duration, and gave rise to what became known as ‘Castramania’.

The two largest encampments comprised about 10,000 soldiers and were both inaugurated on Thursday 28th May 1778. One was established on Cox Heath, just south of Maidstone in Kent. The other was situated on Warley Common, south of Brentwood in Essex. Both camps were terminated, nearly six months later, on 11 November 1778 and both were also visited by King George III and Queen Charlotte.

The most resplendant of these two camps must have been that on Warley Common where, on Tuesday 20 October, a grand spectacular was staged for the benefit of the King and Queen. A royal review of the troops took place and a fierce mock battle was fought on the slopes of Childerditch and Little Warley Commons. The colour and movement of that day was captured by Philip de Loutherbourg in two large oil paintings of the ‘Review’ and the ‘Mock Attack’. These pictures can be found at RCINs 406348, 406349.

Two weeks later, having enjoyed while at Warley Common the lavish hospitality of Lord Petre at Thorndon Hall, the King visited Cox Heath. Reviewing the troops there on 3 November, His Majesty and Queen Charlotte were afterwards entertained at Leeds Castle by the Hon. Mr Fairfax. Although there was no pictorial record of this occasion to match the de Loutherbourg paintings, it was thought, until recently, that this splendid large watercolour by Thomas Sandby entitled ‘The camp on Cox Heath, 1778’ represented the camp in Kent in the summer, some time before the King’s visit.

The title of this landscape appears to have been given as Cox Heath in the early nineteenth-century (c.1811-25) inventory of this collection, but Oppé, when cataloguing the item in the 1940s, expressed doubts about the accuracy of the location of the scene. His uncertainty was founded on the lack of correlation of any of the features in the watercolour with other contemporary views and maps known to be of Cox Heath. It had been suggested to Oppé that the camp at Blackheath in 1780 may have been the subject of the drawing. However, since, at the time he wrote, the group of materials which contained the view was known as the Cumberland Collection (after William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (1725-60) uncle to King George III), Oppé himself inclined to the opinion, also based on stylistic grounds, that the watercolour might represent an earlier camp on Cox Heath which was reviewed by the Duke on 24 September 1754.

Research undertaken during the writing of this catalogue of the military map collection has confirmed Oppé’s doubts and suggests that, on balance, the true location of Sandby’s view is not Cox Heath, even in 1754, but the encampment on Warley Common in 1778. It is not easy to offer a simple reason for what appears to have been an early nineteenth-century mis-identification of the view, but the explanation may lie in the close similarities of the size of the camps, their dates, and the fact that they were both visited by the King and Queen within about two weeks. After about two hundred years of being identified as Cox Heath, the title of this watercolour has now been changed to ‘The camp on Warley Common, 1778’. The basis of the revised title is fivefold and is contained in the clues provided in (1) the alignment of the encampment, (2) the physical landscape, (3) the style and structure of the windmill which occupies the foreground of the panoramic view over the countryside, (4) the architecture of a prominent building, and (5) the position of the temporary booths of suppliers of beer, food, etc. Three of these were highlighted by Oppé In his description of the built landscape: the first was a ‘post-mill with a round house, followed by a ‘large red mansion’ followed by, on the extreme right of the view, 'the houses of a large village’.

The first, and most significant, discrepancy between the watercolour and the Cox Heath site is found in the layout of the encampment. The arrangements of camps were made according to predefined rules and measurements; every yard was accounted for, and alignments were precise and there was a definite ‘front line’ taken up by the men, while officers occupied the rear. On the military plans in General Morrison's volume (RCIN 734032), the position of each regiment was indicated by a rectangle, coloured according to the uniform jackets of the regiment, and the front of the camp was indicated by a thicker line along one side of the rectangle. In pictorial representations, the front of an encamped regiment can usually be identified by the presence of the small flags which were the camp colours. These were always placed at the head of the camp and they can be clearly seen on Sandby’s view. The position of these flags corresponds with the thickened line on the encampment plans.

Plans and contemporary descriptions of the camp on Cox Heath in 1778 describe it as being laid out in a straight line, with the artillery park to the rear of the western end. This can be seen in the map at RCIN 734032.w. The front line of the Cox Heath camp faced the southern edge of the Heath, and the turnpike road to Maidstone ran through the centre of the camp. In contrast, the arrangement of the camp in Sandby's view forms a slight chevron-shaped alignment and there is no evidence of the turnpike road which could be expected to have formed a prominent feature had Sandby’s landscape represented Cox Heath. In the far distance of the view a separate group of tents occupies a space between two wooded areas, while a flanking group of tents occupies the middle distance. Like the Cox Heath camp, the main length of the camp in this view is aligned parallel with the edge of an open space (common or heath). The principal difference is that, whereas the Cox Heath camp faced the edge of the heath, the Warley Common camp had its rear to the edge of the common. Contemporary plans show that the Warley Common encampment was aligned with its rear to the west, while the front line faces east over the common as a whole. In all respects, the configuration of the encampment in Sandby’s watercolour is consistent with the layout of the camp on Warley Common in 1778 as shown in RCIN 734032.x.

The second inconsistency between Sandby’s view and the location of Cox Heath is topographical. The plans show that in order for Sandby to have depicted the front line of the camp on Cox Heath so that the front of the camp faced towards the left (as it does in this view), he would have to have taken his view from the eastern end of the ridge on which the heath was situated. The foreground of Sandby’s landscape is elevated and overlooks the small wooded plain on which the tents are gathered. But the east end of Cox Heath is actually lower than the rest of the heath on which the tents were pitched, and could not, therefore, have provided a raised viewpoint unless artistic licence had been used in the composition. The ground at Cox Heath would have risen in the middle distance and fallen away down a steep escarpment to the left (south), overlooking the river Beult. To the right (north), it would have sloped downhill towards Maidstone. Instead, Sandby’s view, taken from a raised position, looks out over a fairly level area for the whole breadth of the panorama. This, too, is consistent with the topography in the area of Warley Common. In particular, the front line of the camp on the left is consistent with a viewpoint sited near Shenley Common, a raised area immediately south of Brentwood.

Another feature of the physical landscape which is strikingly consistent with the contemporary plans of Warley Camp is the distribution of woodland. These plans (RCINs 7334032.z, 734034.b, 734045.b) show that the artillery park was sited to the east of the southern end of the camp, in an open space framed by Holden Wood and Dame Ellis’s Wood. Sandby’s view shows, in the distance, right of centre, a group of tents framed by woodland, exactly in the place the artillery park would be looked for in any representation of this camp taken from the north. Although any view of the cannon in the artillery park would be obscured by the tents of the Rutland and Artillery regiments, a solitary gun carriage can be discerned in this area of the drawing, lending some support to this interpretation.

The plans also show that the East Kent, North Lincolnshire, Glamorgan and East Suffolk militia were encamped to the east of the main line of tents, on a level area at the foot of a small hill, against a backdrop of Hart’s Wood to the south. Again, Sandby’s view shows just such a combination of tents and physical environment in the middle distance. This distribution of woodland was not present on any of the contemporary plans of Cox Heath. A further physical feature to note on the drawing is the proximity of a hedgerow to the northern end of the line in the foreground of the view; this is consistent with the plans of the Warley Common camp and is not a feature of the Cox Heath camp.

The third inconsistency between Sandby's view and the camp on Cox Heath is his depiction of a windmill, or ‘post-mill’, prominently placed in the left foreground of the drawing. There is no evidence for a windmill in the right location on Cox Heath, in Kent. Sandby has drawn the mill in careful detail, allowing an expert to be able to say that it is typical of an Essex, rather than a Kent windmill. Although the windmill is outside the area shown on the plans of the encampment, two windmills are shown south of Brentwood, near Shenfield Common on Chapman and André’s map of Essex (1777). They stand on a slight eminence overlooking Warley Common to the south, and this position would have afforded the view of the encampment taken by Sandby. The map, if correct, shows that the eastern of the two windmills would have overlooked some buildings. Since these do not appear in the drawing, it is possible that the mill which is depicted represents the western windmill, which, according to the map, stood forward of the first mill, and to the west side of the buildings which would not, therefore, have entered Sandby’s field of vision in the composition of this view. However, the survey sketch (1799) for the Ordnance Survey one-inch map of 1805 shows a slightly different configuration for the adjacent buildings and it may be that some artistic licence has been used in this vicinity. If this was, indeed, the case, it might also explain the too close proximity to the mill, in the drawing, of the road leading from Brentwood down to Warley Common, compared with its representation on the maps. Finally, a similar windmill can be seen to the right of de Loutherbourg's painting of the review at Warley Common (RCIN 406349).

The fourth piece of evidence in support of the identification of the view as that of Warley Common is his depiction of a substantial residence. Taking the mill as a base, there can be seen in the view, at an angle of about 35 to 40 degrees to the south-east (extreme left of the picture), Oppé's ‘large red mansion’. A similar angle taken from the windmill on Chapman and André's map, or the Ordnance Survey one-inch map (1805), or the modern Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 Landranger (sheet 177), when projected along the ray, arrives at Thorndon Hall. Although the building is placed in the middle distance in the watercolour, Sandby has bestowed sufficient attention on the detail of the architecture for there to be little doubt about the accuracy of the identification of the mansion as Thorndon Hall, one of James Paines’s largest country houses. The Hall was built between 1764 and 1770 for the Ninth Lord Petre (Robert Eward Petre, 1742-1801). It was a large structure, built to a Palladian design with a pair of service wings linked to the main block. These wings, which curved round to the north, can be discerned in Sandby’s view of the north front, with the five chimneys above.

The final piece of evidence considered in this assessment is what Oppé termed the houses of a ‘large village’. The plans and contemporary topographical maps of Warley Common clearly show that, although there was an occasional building in this area, there was certainly no large village; the same was true of Cox Heath. However, it is known from contemporary descriptions that this area of the Warley Common camp was covered by the huts and booths of suppliers of ‘necessaries’ to the soldiers. Indeed, the Chelmsford Chronicle for Friday 18 September printed an account of a fire in one of these huts which spread and ‘communicating to the other huts, destroyed upward of fifty of them, besides a butcher’s shop, a brewhouse and three public houses’. The account also mentioned the fortunate fact that the wind was from the east ‘otherwise the whole rear line would have been burnt’. This is independent corroboration that the rear of the line was was adjacent to the huts and buildings, as depicted on the plans, and it is consistent with Sandby’s view. It seems, then, that Oppé’s ‘large village’ can be accounted for by the presence of numerous temporary buildings erected with the sole purpose of serving the encamped army. The camp at Cox Heath was, doubtless, also served by local shopkeepers, but there seems to be no view depicting their presence.

There remains to be described one feature of the built landscape which was not commented on by Oppé. This is a row of buildings, right of centre, on the crest of the lower slopes of Shenley Common. These do not appear to be large structures, when measured against the figures of people in the vicinity and it is possible that they were also temporary booths and huts, erected for the duration of the camp. Otherwise, Chapman and André’s map of 1777, and the Ordnance Survey one-inch map of 1805, both show a small group of buildings in this general locality, although possibly fewer in number on the map than are represented in the watercolour.

Taken as a whole, the evidence in favour of the identification of this view as the encampment on Warley Common in 1778 is persuasive. First, the alignment of the encampment is wholly consistent with contemporary plans of the camp on Warley Common. Second, the physical landscape accords well with the known topography of the area in the eighteenth century. Third, the buildings at the rear of the camp can be explained by contemporary descriptions of the booths, huts and structures which were erected for the duration of the camp, and the large, imposing house in the left of the drawing bears a convincing resemblance to Thorndon Hall. Finally, the windmill itself is typical of an Essex mill. The principal inconsistency in the evidence is the positional relationship of the windmill to the adjacent road, but this is outweighed by the fact that none of the features in this view is consistent with the camp or landscape of Cox Heath in 1778.

Thomas Sandby (1721-98) (artist)

48.0 x 147.1 cm (sight)

64.0 x 162.2 cm (frame, external)

Manuscript title:

None

Annotations:

The Camp on Cox Heath, 1778

K. Mil. dummy sheet:

[No RCIN; not on fiche.] Title [ink:] A drawn View of the Camp at Cox Heath 2 sheets / A Roll ... [bp:] 5 Table 2.d / [George III heading, bp and red ink:] XIV/37 Encampment on Cox Heath 28 May - 11 Nov. 1778 / [bp, Christian Bailey's hand:] RL: 14729 [in another hand, ? Ruth Cohen:] = K.Mil.XIV.037.b / [ CMB 's hand:] (Sandby) p/f 53 Cup R / [ink, 18thC hand:] no title. Watermark Fleur-de-lys in crowned shield, the letters B&W below. Size (s) 471 x 323.

George III catalogue entry:

Cox Heath A drawn View of the Camp on Cox Heath in 1778. 2 sheets [The same entry appears under the heading Encampments’

Subject(s)

Great Warley Street, Essex, UK (51°35'34"N 00°17'03"E)

Bibliographic reference(s)

R. Tickell, ‘Prologue To the Camp’, a poem published in The Universal Magazine, November 1778, p.263, and also in The Gentleman’s Magazine, October 1778, p.487

O. Millar, The later Georgian pictures in the collection of Her Majesty The Queen, London 1969; entries 932 (plate 83) and 933 (plate 84)

A.P. Oppé, The drawings of Paul and Thomas Sandby in the collection of His Majesty The King at Windsor Castle. Oxford 1947, no.158, p.47.

The Universal Magazine, July 1778, p.50: ‘The regiments at Coxheath form a straight line ...’.

I am indebted to the late Stuart Mason, who provided me with the extract from the Chelmsford Chronicle, and whose own article ‘Summer camps for soldiers:1778-1782’, Essex Journal, vol.33, no.2,1998, pp.39-45, describes the camps in Essex, including the royal visit to Warley Common and Thorndon Hall, in great detail.

I am most grateful to Luke Bonwick for his technical advice on the windmills of Essex, and for his identification of the windmill in Sandby’s view as an Essex mill.

Ordnance Surveyor’s Drawing 138, Map Library British Library, surveyed in preparation for the publication of sheet 1 of the Ordnance Survey Old Series one-inch map.

The identification of the large building as Thorndon Hall was independently suggested by John Harris. For a description and illustrations of the building see P. Leach, ‘James Paine’, Studies in Architecture, edited by J. Harris and A. Lang, Vol XXV, London 1988, pp.80-2

Page revisions

27 July 2024

Current version

Replaced main image